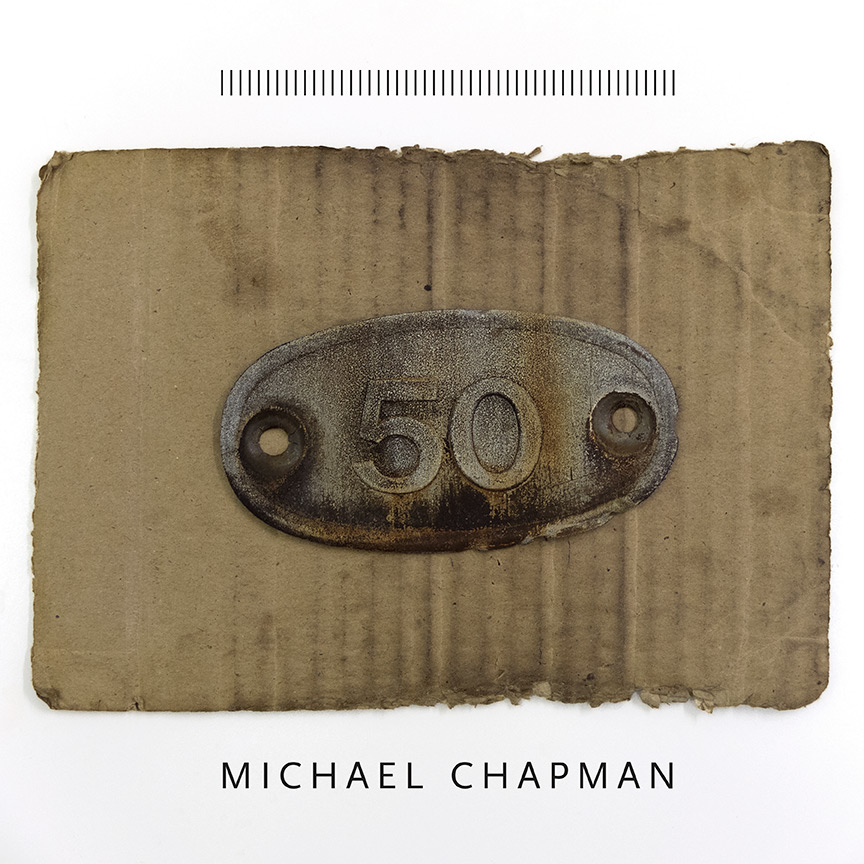

Michael Chapman

50 (Paradise Of Bachelors)

Contact Stephanie Bauman about Michael Chapman

Veteran British songwriter and guitar sage Michael Chapman ranks among the innovative midcentury English guitarists—Davey Graham, Richard Thompson, and Michael’s old friend Mike Cooper are others—who transposed the atmosphere and syntax of the blues to a British context through reinvention and deconstruction rather than imitation. But Chapman uniquely deploys his liquid virtuosity and his resonant, slurred Yorkshire burr as vehicles for his mournful (and often barbed) musings on the pleasures and perils of hard living. His music feels suffused (like Stanford’s work) with the crooked logic, unfulfilled longing, and existential danger of dreams, shaded with his own wry sensibility of Northern darkness. Like a peaty whiskey (or Bob Dylan), the smoky gravitas of his playing and singing has grown more trenchant and entrenched with age; no one else sounds like him.

It’s difficult not to describe Michael’s long career and his vast, masterful body of work obliquely, by reeling off his musical genealogy, the astounding roll call of collaborators, comrades, and disciples with whom he’s shared stages, studios, and his sturdy songs. His emergence in 1967, alongside Wizz Jones, as a self-taught jazz freak, recovering art-school student, and part-time photography teacher on the Cornish folk circuit preceded a series of classic late 1960s and ’70s albums for Harvest, Deram, and Decca. (But whatever you do, don’t call him a folkie; he feels more kinship with the improvisatory outer orbits of jazz, blues, and the avant-garde.)

A peer of legends like Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, and Roy Harper—but arguably more mercurial and less classifiable over the long haul than any of them—Chapman is probably the only musician in history to have played and recorded with Mick Ronson, Elton John, and Thurston Moore. (True stories: David Bowie enlisted Ronson in the Spiders from Mars as a direct result of his superb playing on Chapman’s Fully Qualified Survivor,John Peel’s favorite album of 1970. Elton John tried to recruit Michael to his band thereafter, but producer Gus Dudgeon interfered.) Following a millennial resurgence and reissue campaigns by the Light in the Attic andTompkins Square labels, Michael’s songs have recently been covered by Lucinda Williams, Kurt Vile, Hiss Golden Messenger, Meg Baird, and William Tyler, and he has performed and toured with younger devotees including Bill Callahan, Jack Rose, Daniel Bachman, and Ryley Walker. But this litany of comrades and admirers is only one vector by which to chart the undiluted potency of Chapman’s artistry and its deep currents of influence on three generations of musicians.

His new record 50, titled to commemorate fifty years of touring—and released four days before Michael’s seventy-sixth birthday—stands as a formidable monument of retrospection and introspection in his adventurous catalog (last we counted, approaching fifty records.) A return to the gloriously ragged kineticism ofRainmaker (1969), Fully Qualified Survivor (1970), Wrecked Again (1971), and Savage Amusement (1976), Michael’s first “American record”—an elusive goal for decades—embodies his undeniable late career masterpiece. It is his first album in years with a full band, assembled around the versatile core group of friend and producer Steve Gunn (who also contributes guitar, drums, and vocals): Nathan Bowles (drums, banjo, keys, vocals; Pelt, Black Twig Pickers); James Elkington (guitar, piano; Jeff Tweedy, Richard Thompson), and Jimy SeiTang (bass, synthesizers, vocals; Rhyton, Stygian Stride). Michael’s dear friend and fellow UK songwriting luminary Bridget St John furnished her gorgeous, shivering vocals, a dramatic counterpoint to Chapman’s road-worn gruffness. Gunn’s touring bassist and longtime engineer Jason Meagher (No-Neck Blues Band) recorded and mixed at hisBlack Dirt Studio in Westtown, New York. The inherently collaborative nature of 50 shows in its ambition and execution; never has Michael ceded such generous control to other musicians, and he sounds both invigorated and liberated as a result. Gunn’s and Elkington’s guitars knit with Chapman’s in easy intergenerational dialogue; sparks fly.

The album includes both radical reinterpretations of obscure material from Michael’s catalog as well as three new compositions: “Sometimes You Just Drive,” “Money Trouble,” and “Rosh Pina.” A longstanding but freshly urgent preoccupation with (as Michael sings in a beloved early tune) “time past and time passing” is evident straightaway, from the album title and the first line of the first song through the final lyric of the record. Never before in his storied career has Chapman gazed so steadily into the abyss of time lost and regained; never before has he engaged so intimately with his legacy and the changing meanings of his own music over time. That he manages to do so without succumbing to nostalgia or sentimentality bears testament to the steely fortitude of his ruminative, tough-minded songs, which survey both inscape and landscape with the same stoical detachment.

Chapman’s spare writing on 50 displays a refined economy of gesture, often unfolding in episodic parables (see “The Prospector” and “A Spanish Incident”), wherein regret and redemption elide symbolically in a sublime chiaroscuro self-portrait, more shadow than light, his world-weary whispers assuming the incandescent power of prophecy. The boozy good humor and resignation of “Money Trouble” and “A Spanish Incident” find traces of comedy and camaraderie amid the absurdity of a world in which we lose our words, our way, our faith. The menace and anxiety of “Sometimes You Just Drive,” which poignantly conflates the End of Days with the end of one man’s days, and “Memphis in Winter,” a hellish Bluff City travelogue, contrast with the naked vulnerability and remorse of “Falling from Grace” and “Navigation.” In lead single “That Time of Night” Michael confesses, movingly, “you know I don’t scare easy, but I do get scared.”